Saturday, November 23, 2013

Wanda Coleman, acclaimed L.A. poet, has died at 67

It is a sad day for our poet community with Wanda's powerful, witty and charismatic voice now silent.

R.I.P. Wanda Coleman!

Wanda Coleman's husband Austin Straus has announced that there will be a memorial for his late wife. Details forthcoming.

Read the LA Times article here:

http://www.latimes.com/books/jacketcopy/la-et-jc-poet-wanda-coleman-67-has-died-20131123,0,2667185.story#axzz2lVBr2fLi

Read the LA Times obituary here:

http://www.latimes.com/obituaries/la-me-wanda-coleman-20131124-1,0,3349194.story#axzz2lWpxx7Lr

Wednesday, November 13, 2013

Event has been postponed for the time being. A new date will be announced for the Austin Straus talk on Monday, November 18, 4:30pm to 5:30pm, at Occidental College

Event has been postponed for the time being. A new date will be announced!

There will be a talk with Austin Straus on Monday, November 18, 4:30pm to 5:30pm, at Occidental College 1600 Campus Rd. Los Angeles, CA 90041 to formally open an exhibition of his works.

http://www.oxy.edu/events/

There will be a talk with Austin Straus on Monday, November 18, 4:30pm to 5:30pm, at Occidental College 1600 Campus Rd. Los Angeles, CA 90041 to formally open an exhibition of his works.

Paintings/Collages & Unique Books

by Austin Straus

Special Collections, Occidental College Library

Paintings/Collages & Unique Books by Austin Straus

Main Floor, Library

Open through January 31, 2014.

Main Floor, Library

Open through January 31, 2014.

"The works shown here are a small sampling of my output spanning more than 50 years. I have been experimenting with burning techniques since childhood. I love the feeling of multi-layered aerial views which suggest maps, roads, veins and arteries, and the inner complexity of the brain and mind. Among my many influences are layered and weathered posters and billboards, and the work of Schwitters, Rotella, Tobey, Kandinsky, Klee, and Stuart Davis. In many of my collages I try to suggest the multiplicity, ambiguities, and interplay of memories and dreams. (Thus: Rosetta Speaks, Boy in a Sailor Suit, Panther Song and Violators.) In others, I map cities and ruins. And in Las Vegas I tried to suggest the glitter and gold of that overwhelming money machine. I started making artists’ books more than 30 years ago. Recently, I’ve been experimenting with burning books (see my additional statement near the vitrine). I love the idea of see-through multi-level pages that can be turned by the reader-viewer, with a beautiful and powerful surprise on each page. Many of my books are sculptural artworks in book form. Other books are albums of paintings , collages, and drawings." -- Austin Straus.

There will be a talk with Austin Straus on Monday, November 18, 4:30pm to 5:30pm, to formally open the exhibition of his works. More info here.

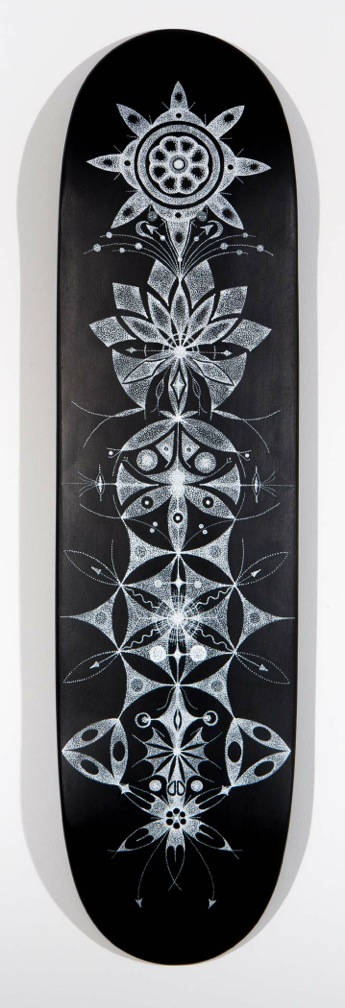

Photo: Violators, mixed media on board, by Austin Straus.

Wednesday, November 6, 2013

MOBY DICK Screening at Beyond Baroque on Thursday, 11-7-13

TOMORROW NIGHT! We're screening the Gregory Peck version of MOBY DICK (with screenplay by Ray Bradbury). Reception at 7:30PM, screening at 8:00PM.

Saturday, October 19, 2013

READ THE NY TIMES ARTICLE ON MIKE KELLEY

This Show’s as Big as His Career

10/17/13

Read the link:

http://mobile.nytimes.com/2013/10/18/arts/design/mike-kelley-a-survey-at-moma-ps1-in-queens.html

or read the article here:

October 17, 2013By HOLLAND COTTER

Plainly put, the Mike Kelley retrospective, fresh from Europe to MoMA PS1, knocks everything else in New York this fall right out of the ring. It’s immense, filling 40,000 square feet of gallery space, including a sub-basement boiler room. And it’s that extremely rare thing, a huge show that should be huge. Kelley earned this blowout; his work sustains it.

In a three-decade career, cut off abruptly by his suicide, at 57, last year, Kelley did it all, in terms of genre: performance, painting, drawing, printmaking, sculpture, video, installation, sound art and writing. And he wove together — twisted together — all of that into what amounted to a single conceptual project based on recurrent themes: social class, popular culture, black humor, anti-formalist rigor and, though rarely acknowledged, a moral sense, unshakably skeptical, that ran through everything like a spine.

Kelley often complained that people confused his art and his life, yet he constantly mined his past for material.

He was born in 1954 into a working-class Irish Catholic family in suburban Detroit. He was a bookish kid who aspired be a writer but feared he didn’t have the chops, so he went for art. His family scorned his ambitions, but his push-back, perversity-savoring personality saw him through.

Instead of doing sports, he learned to sew.

Although straight, he acted queer, and once wore a dress to school.

His early life and art were both shaped by his resistance to authority in any form, at home, in school and in the world. Normal was a no-go zone. His youthful heroes included William Burroughs, Sun Ra, Gertrude Stein, Basil Wolverton, Abbie Hoffman and the Cockettes.

In high school and college, he hung with the freaks as the utopian tide of hippiedom receded, and anarchist punk rippled in. While an art student at the University of Michigan, in Ann Arbor, he and some friends started a noise band called Destroy All Monsters, which was more about art and language than about music. It confirmed his interest in performance, which he carried with him to graduate school at the California Institute of the Arts, or CalArts, in Los Angeles County.

When he arrived there in 1976, CalArts was a bastion of Conceptualism, art about thinking, to which he added acting and making. Still in a performance groove, he invented musical instruments — he called them “performative sculptures” — that plunked or beeped or just sat around. For his graduate show, and to everyone’s puzzlement, he built a set of wooden birdhouses, of a sort that might have emerged from high school shop class and to which he gave droll extra-avian titles like “Gothic Birdhouse” and “Catholic Birdhouse.”

These are some of the earliest works in the show. They introduced a vernacular crafts aesthetic that had virtually no connection to any art school art at that time but that would become a staple for Kelley. They also carried critical associations with domesticity, maleness and childhood, which were among his recurrent subjects.

To Kelley, the conventional notion that childhood was a benign, prefallen state, or that humans could ever have a state, was delusional. He skewered it again and again. For a 1983 video called “The Banana Man,” he borrowed a character from the television show “Captain Kangaroo” and turned him into a crazed camp clown passing out sex tips instead of sweets.

In 1987, as part of a multimedia project called “Half a Man,” Kelley made sculptures from hand dolls and stuffed animals that he found in thrift shops. Set out in erotic tableaus, sewn together in cruelly jammed clusters, shrouded under old blankets and afghans, they evoked sadness and anger in viewers, of an intensity that surprised Kelley, who meant them to register as provocative but emotionally ambiguous.

These sculptures, which appeared in his 1993 Whitney Museum survey, became his best-known images because they could function as stand-alone objects, a thing critics knew how to write about and galleries knew how to sell. By contrast, the fertile but less graspable range of work that led up to them was dismissed or ignored, and it’s this art that the PS1 show most valuably restores to us.

A lot of it was performance, and doesn’t survive. Kelley refused to have most of his early performances videotaped, insisting that they were one-time-only events, period. Yet many of these events generated sculptures, paintings and installations, and these are still around. One installation, the 1985-86 “Plato’s Cave, Rothko’s Chapel, Lincoln’s Profile,” designed as performance environment, is a classic Kelley blend of scatology and eschatology, with paintings and drawings referring to bodily functions, Afro wigs, Nazis, gender confusion and Jesus.

Like so much of Kelley’s output, this work is meticulously done but looks as if it should smell bad. It’s perfectly horrid. And great.

Another complex environment, “The Sublime,” from 1984, is essentially a poison pen letter to spiritual transcendence, or art’s claim to it, and is punctuated by a trippy drawing of what could be the Big Bang. It looks pretty cosmic until you notice that the energy waves have a knotty-pine pattern, familiar from rec room walls, and the source of their radiation is a tiny, centrally placed sketch of a suburban home.

Home, in one form or another, is what Kelley kept coming back to.

Sometimes home was blue-collar America, as in the 1987 installation “From My Institution to Yours,” which introduced loading dock graffiti and militant union emblems into a rarefied museum environment.

Home was also school. Kelley spent most of his life either studying or teaching. For the 1995 tabletop piece “Educational Complex,” he created architectural models of every school he ever attended. (If you crawl under the table and look up, you can see the CalArts basement.)

And long after he moved out, Detroit, too, was still home. In 2001, for the city’s tricentennial celebration, he recreated a statue of the astronaut John Glenn that stood in his high school library, piecing the new version together from kitchen crockery and glassware shards dredged from the Detroit River. In 2010, he built a full-scale model of the house he grew up in and had it driven through town on a flatbed truck.

And there was always that psychic terrain, American childhood, the abject state you both didn’t want to revisit and couldn’t escape from.

His largest project ever, the 2005 “Day Is Done,” is basically a multimedia evocation of that state. And far from being a sentimental immersion, it feels like an act of aggravated assault. Inspired by the New Age faith in repressed memory of traumatic abuse, the piece consists of some two dozen filmed re-creations of high school yearbook photos — of sports meets, pageants, proms — with each blast from the past reincarnated as a full-color, hellishly high-volume video.

Finally, home is a utopian fantasy. The “Kandor Project” is a series of sculptures named for the Kryptonite city where Superman was born and which, according to the DC Comics of Kelley’s youth, the Man of Steel kept preserved in miniature form under glass. From 1999 to 2011, Kelley created numerous variations on the Kandor image — the series was unfinished at his death — all cast in colored resin and either encased in sleek containers or set on funky faux-rock stands.

These late sculptures are placed near the beginning of the show, which was organized by Ann Goldstein, director of the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam (from an initial concept by Eva Meyer-Hermann) and installed in New York by Connie Butler and Peter Eleey. It feels odd to find them there, because they’re uncharacteristic of Kelley’s art overall.

Like the wildly elaborate “Day Is Done,” they date from after the time Kelley signed on with the Gagosian Gallery in 1995. He was now a star with a big budget, and the work suddenly looks expensive, machine-tooled, overproduced. The Kandors have the luxury-line gloss of Jeff Koons junk art. What saves them is that they have Kelley’s history behind them.

What a history. No show can encompass it. I wonder what Kelley in the end would have made of it. A committed insurrectionist, he saw the very concept of a counterculture vanish before his eyes. He saw an art world virtually institutionalize the class-based exclusions he despised. He saw art itself retreat from existential politics to escapist playtime.

Of course, it would have been nice — righteous — if Kelley’s retrospective were on 53rd Street, though MoMA says scheduling dictated otherwise, and, really, he makes more sense in a former public school in Queens where young artists congregate.

They’ve always been his best audience. The list of those he has influenced is already long, and it could be — art changes, after all — that his true progeny are still to come.

“Mike Kelley” runs through Feb. 2 at MoMA PS1, 22-25 Jackson Avenue, at 46th Avenue, Long Island City, Queens; (718) 784-2084, momaps1.org.

In a three-decade career, cut off abruptly by his suicide, at 57, last year, Kelley did it all, in terms of genre: performance, painting, drawing, printmaking, sculpture, video, installation, sound art and writing. And he wove together — twisted together — all of that into what amounted to a single conceptual project based on recurrent themes: social class, popular culture, black humor, anti-formalist rigor and, though rarely acknowledged, a moral sense, unshakably skeptical, that ran through everything like a spine.

Kelley often complained that people confused his art and his life, yet he constantly mined his past for material.

He was born in 1954 into a working-class Irish Catholic family in suburban Detroit. He was a bookish kid who aspired be a writer but feared he didn’t have the chops, so he went for art. His family scorned his ambitions, but his push-back, perversity-savoring personality saw him through.

Slide Show | Maverick and Scavenger A Mike Kelley retrospective completely fills MoMA PS1.

Although straight, he acted queer, and once wore a dress to school.

His early life and art were both shaped by his resistance to authority in any form, at home, in school and in the world. Normal was a no-go zone. His youthful heroes included William Burroughs, Sun Ra, Gertrude Stein, Basil Wolverton, Abbie Hoffman and the Cockettes.

In high school and college, he hung with the freaks as the utopian tide of hippiedom receded, and anarchist punk rippled in. While an art student at the University of Michigan, in Ann Arbor, he and some friends started a noise band called Destroy All Monsters, which was more about art and language than about music. It confirmed his interest in performance, which he carried with him to graduate school at the California Institute of the Arts, or CalArts, in Los Angeles County.

When he arrived there in 1976, CalArts was a bastion of Conceptualism, art about thinking, to which he added acting and making. Still in a performance groove, he invented musical instruments — he called them “performative sculptures” — that plunked or beeped or just sat around. For his graduate show, and to everyone’s puzzlement, he built a set of wooden birdhouses, of a sort that might have emerged from high school shop class and to which he gave droll extra-avian titles like “Gothic Birdhouse” and “Catholic Birdhouse.”

These are some of the earliest works in the show. They introduced a vernacular crafts aesthetic that had virtually no connection to any art school art at that time but that would become a staple for Kelley. They also carried critical associations with domesticity, maleness and childhood, which were among his recurrent subjects.

To Kelley, the conventional notion that childhood was a benign, prefallen state, or that humans could ever have a state, was delusional. He skewered it again and again. For a 1983 video called “The Banana Man,” he borrowed a character from the television show “Captain Kangaroo” and turned him into a crazed camp clown passing out sex tips instead of sweets.

In 1987, as part of a multimedia project called “Half a Man,” Kelley made sculptures from hand dolls and stuffed animals that he found in thrift shops. Set out in erotic tableaus, sewn together in cruelly jammed clusters, shrouded under old blankets and afghans, they evoked sadness and anger in viewers, of an intensity that surprised Kelley, who meant them to register as provocative but emotionally ambiguous.

These sculptures, which appeared in his 1993 Whitney Museum survey, became his best-known images because they could function as stand-alone objects, a thing critics knew how to write about and galleries knew how to sell. By contrast, the fertile but less graspable range of work that led up to them was dismissed or ignored, and it’s this art that the PS1 show most valuably restores to us.

A lot of it was performance, and doesn’t survive. Kelley refused to have most of his early performances videotaped, insisting that they were one-time-only events, period. Yet many of these events generated sculptures, paintings and installations, and these are still around. One installation, the 1985-86 “Plato’s Cave, Rothko’s Chapel, Lincoln’s Profile,” designed as performance environment, is a classic Kelley blend of scatology and eschatology, with paintings and drawings referring to bodily functions, Afro wigs, Nazis, gender confusion and Jesus.

Like so much of Kelley’s output, this work is meticulously done but looks as if it should smell bad. It’s perfectly horrid. And great.

Another complex environment, “The Sublime,” from 1984, is essentially a poison pen letter to spiritual transcendence, or art’s claim to it, and is punctuated by a trippy drawing of what could be the Big Bang. It looks pretty cosmic until you notice that the energy waves have a knotty-pine pattern, familiar from rec room walls, and the source of their radiation is a tiny, centrally placed sketch of a suburban home.

Home, in one form or another, is what Kelley kept coming back to.

Sometimes home was blue-collar America, as in the 1987 installation “From My Institution to Yours,” which introduced loading dock graffiti and militant union emblems into a rarefied museum environment.

Home was also school. Kelley spent most of his life either studying or teaching. For the 1995 tabletop piece “Educational Complex,” he created architectural models of every school he ever attended. (If you crawl under the table and look up, you can see the CalArts basement.)

And long after he moved out, Detroit, too, was still home. In 2001, for the city’s tricentennial celebration, he recreated a statue of the astronaut John Glenn that stood in his high school library, piecing the new version together from kitchen crockery and glassware shards dredged from the Detroit River. In 2010, he built a full-scale model of the house he grew up in and had it driven through town on a flatbed truck.

And there was always that psychic terrain, American childhood, the abject state you both didn’t want to revisit and couldn’t escape from.

His largest project ever, the 2005 “Day Is Done,” is basically a multimedia evocation of that state. And far from being a sentimental immersion, it feels like an act of aggravated assault. Inspired by the New Age faith in repressed memory of traumatic abuse, the piece consists of some two dozen filmed re-creations of high school yearbook photos — of sports meets, pageants, proms — with each blast from the past reincarnated as a full-color, hellishly high-volume video.

Finally, home is a utopian fantasy. The “Kandor Project” is a series of sculptures named for the Kryptonite city where Superman was born and which, according to the DC Comics of Kelley’s youth, the Man of Steel kept preserved in miniature form under glass. From 1999 to 2011, Kelley created numerous variations on the Kandor image — the series was unfinished at his death — all cast in colored resin and either encased in sleek containers or set on funky faux-rock stands.

These late sculptures are placed near the beginning of the show, which was organized by Ann Goldstein, director of the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam (from an initial concept by Eva Meyer-Hermann) and installed in New York by Connie Butler and Peter Eleey. It feels odd to find them there, because they’re uncharacteristic of Kelley’s art overall.

Like the wildly elaborate “Day Is Done,” they date from after the time Kelley signed on with the Gagosian Gallery in 1995. He was now a star with a big budget, and the work suddenly looks expensive, machine-tooled, overproduced. The Kandors have the luxury-line gloss of Jeff Koons junk art. What saves them is that they have Kelley’s history behind them.

What a history. No show can encompass it. I wonder what Kelley in the end would have made of it. A committed insurrectionist, he saw the very concept of a counterculture vanish before his eyes. He saw an art world virtually institutionalize the class-based exclusions he despised. He saw art itself retreat from existential politics to escapist playtime.

Of course, it would have been nice — righteous — if Kelley’s retrospective were on 53rd Street, though MoMA says scheduling dictated otherwise, and, really, he makes more sense in a former public school in Queens where young artists congregate.

They’ve always been his best audience. The list of those he has influenced is already long, and it could be — art changes, after all — that his true progeny are still to come.

“Mike Kelley” runs through Feb. 2 at MoMA PS1, 22-25 Jackson Avenue, at 46th Avenue, Long Island City, Queens; (718) 784-2084, momaps1.org.

Correction: October 19, 2013

An art review on Friday about “Mike Kelley,” at MoMA PS1 in Queens, misstated the year of Kelley’s work “Day Is Done.” It is from 2005, not 1995.

Tuesday, October 8, 2013

Cancer Treatment Fundraiser for one of our staff members!

Dear BB supporters,

we need your help in raising funds for one of our team members who is undergoing cancer treatment at this time.

*** This is an online and ongoing fundraiser and last day to donate is November 10th, 2013. ****

Just click on this link, which will bring you to the donation page:https://

In May 2013, Annette Geisler was diagnosed with a rare small cell carcinoma on her thyroid that required surgery, radiation and currently ongoing chemo therapy at the Disney Cancer Center in Burbank, CA. She should be done with everything by the end of this year. Please read the fundraiser link for more details, on how to donate (paypal option is enabled) and if you want to see what's the latest news about her.

Please know that no contribution is too small and every little bit will help her and her family. They are grateful for everyone who helps with a financial contribution to make sure that their awesome mom will soon be able to enjoy life to the fullest again.

Please feel free to share the link with friends and family.

With a lot of gratitude to all of you for your support, hugs and prayers we say 'THANK YOU' - also in the name of Annette!

Your BB Team

Saturday, October 5, 2013

Interview with Beyond Baroque's Poet-In-Residence, Will Alexander

Will Alexander

Will Alexander is a poet whom critics have not been able to categorize easily. An African-American child of the post-World War II baby boom who grew up in south central Los Angeles, he also does not fit any clichéd image of that generation's avant-garde poets. The son of a World War II veteran, Alexander was influenced by the revolutionary struggles of the Third World that first inspired his father during a military tour of the Caribbean.

Born in Los Angeles, Alexander has remained a lifetime resident of the city. Although he received a B.A. degree in English and creative writing, he has followed his own direction in his writing and painting.

Alexander's first work to attract critical attention was Asia & Haiti.

Until the mid-1990s, he made his living in an assortment of low-paying jobs. He has since given readings of his work and held artist-in-residence posts at various colleges and is now poet-in-residence at Beyond Baroque.

Here is his latest interview with htmlgiant we are happy to share with you:

8 November, Friday - 8:00 PM EZRA POUND MARATHON

Looking for participants and piano player!

Day one of the Ezra Pound Marathon features the master’s famous short poems and selected cantos (there are 120), mostly the best and most famous ones. Directed and hosted by NEIL FLOWERS.In the Mike Kelley Gallery.Special note: Anyone interested in participating in this reading of Pound's Cantos, should contact the Director of the reading at the following e-address: flowersneil4494@yahoo.com. The Director is also seeking a pianist familiar with classical music to play Canto LXXV, which is a musical score. A piano will be provided.

Your BB Team

Day one of the Ezra Pound Marathon features the master’s famous short poems and selected cantos (there are 120), mostly the best and most famous ones. Directed and hosted by NEIL FLOWERS.In the Mike Kelley Gallery.Special note: Anyone interested in participating in this reading of Pound's Cantos, should contact the Director of the reading at the following e-address: flowersneil4494@yahoo.com. The Director is also seeking a pianist familiar with classical music to play Canto LXXV, which is a musical score. A piano will be provided.

Your BB Team

Wednesday, September 25, 2013

SUNDAY (9/29) Triathalon in Venice will effect traffic!

The Triathlon will begin at Venice Beach at 6:50 am with the swim segment. The bike course will shut down Venice Blvd from the beach to the 10, Fairfax from the 10 to Olympic, and Olympic from Fairfax to STAPLES Center. Please note, there will be NO CROSSING POINTS on this year's course.

There will be a rolling open from West to East as the athletes finish the race. All streets will be opened by noon. In the Venice Beach area, the streets will be the first to open at approximately 9:45 AM.

There are no freeway closures. We recommend you go to your nearest freeway on-ramp to the 405 to travel north or south, and the 10 to travel east and west.

| Beyond Baroque will be in booth B3. Our reading takes place 5-5:30 and features Dennis Cruz, Michael C Ford, and Doug Knott. West Hollywood Book Fair celebrates its 12th edition on Sunday, September 29th. This year’s festival will feature literature, art, music, performance and community in an eclectic presentation. The program will welcome treasured Southern California literary luminary, T.C. Boyle, who will present his brand-new collected stories. The ever-entertaining Boyle is sure to be a Book Fair highlight. Many other terrific writers will perform and discuss new and recently published works, including Debbie Reynolds, William Friedkin, Lynda Obst, Victoria Chang, Aaron Hartzler, D.H. Pelligro, Veronica Reyes, and many more to be announced. |

Friday, September 20, 2013

Saturday, September 28, 2013 marks the third annual global event for 100 Thousand Poets for Change!

BEYOND BAROQUE IS PROUD TO SPREAD THE WORD!

COME AND JOIN US!

SCROLL DOWN FOR ALL THE INFO YOU NEED TO KNOW!

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE

Massive Global Movement Gives Voice to Local Issues

through Music, Art, Photography, Poetry, Mime and More

Over 550 Events Planned in 100 Countries for

100 Thousand Poets for Change

Dear Friends and Writers,

The Los Angeles Poet Society is proud to organize the 3rd Annual 100 Thousand Poets for Change event in Los Angeles, CA!

100 Thousand Poets for Change is a global movement, grassroots in origin, spreading the message of truths in the need for change. As a planet we come together at the local level, organize our masses and show that we are not going to sit idle while our world seeps and weeps for change.

(From the official press release by 100TPC Headquarters):

– September 28, 2013 marks the third annual global event for 100 Thousand Poets for Change, a grassroots organization that brings communities together to call for environmental, social, and political change within the framework of peace and sustainability. An event that began primarily with poet organizers, 100 Thousand Poets for Change has grown into an interdisciplinary coalition with year round events which includes musicians, dancers, mimes, painters and photographers from around the world.

Local issues are still key to this massive global event as communities around the world raise their voices on issues such as homelessness, global warming, education, racism and censorship,through concerts, readings, lectures, workshops, performances and other actions. But these locally focused events have taken on a more continuous and expansive form through the new disciplines represented this year. More and more organizers and participants of the one day, annual event are making plans to continue their actions after September 28. Many have formed groups in their cities that will continue to work year round towards the goals their community seeks.

“Peace and sustainability are major concerns worldwide, and the guiding principles for this global event,” said Michael Rothenberg, Co-Founder of 100 Thousand Poets for

Change. “We are in a world where it isn't just one issue that needs to be addressed. A common ground is built through this global compilation of local stories, which is how we

create a true narrative for discourse to inform the future.” --

Los Angeles will hold 2 events, including over 50 Poets and Musicians for Change, including:

Amy Uyematsu

Richard Modiano

Laurel Ann Bogen

Eric Priestly

Poppas Kitchen [official band of Fast Times at Ridgemont High star, "Mike Damone", Bob Romanus]

Will Alexander

Pam Ward

Creative Aging Activist and Poet, Norman Molesko

Eleanor Goldfield Swede of The Rooftop Revolutionaries

Julio the Conga Poet

Antonieta Villamil

Beyond Baroque in Venice, CA will hold events on September 28th, from 12pm to 8pm and will include:

- --- Marathon poetry reading for Change voicing issues on: homelessness, prison system, judicial system, ageism environmentalism, naturalism, social consciousness, immigration, discrimination, & more!

--- PICNIC for PEACE on the Beyond Baroque lawn! We are asking for blanket donations to decorate the lawn! All donated blankets will be washed and given to the homeless of Venice Beach.

--- CHALK the WALKS of Beyond Baroque! Get your art on and be creative, share your message for CHANGE!

--- 100 Mil Poetas por el Cambio! A Spanish segment hosted by Antonieta Villamil

--- PLUS! Poetry Potluck in the Poet's Garden! Bring your favorite treat and enjoy some of ours!

$5 donation at the door. All proceeds will go to Beyond Baroque and assist in funding the Technical Equipment for the event.

100 Thousand Poets | Musicians for Change will be live-streaming and recorded for later viewing on: www.ustream.tv/channel/the-

100 Thousand Poets for Change is a Global Movement, recognized as the largest Poetry reading in the WORLD and archived by Stanford University's LOCKSS program.

Bob's Espresso Bar (owned by Robert "Bob" Romanus)in North Hollywood, CA will hold events on September 29th, from 2pm to 6pmand will include words from poets and musicians for change, to include:

Poppas Kitchen [official band of Fast Times at Ridgemont High star, "Mike Damone", Bob Romanus]

Cklara Moradian

Apryl Skies

Mary Mann

Radomir V. Luza

Jessica Wilson

Judy Barrat

Amanda Reyna

The Whale

Juan Cardenas

100 Thousand Poets | Musicians for Change will be live-streaming and recorded for later viewing on: www.ustream.tv/channel/

100 Thousand Poets for Change is a Global Movement, recognized as the largest Poetry reading in the WORLD and archived by Stanford University's LOCKSS program.

OFFICIAL 100 THOUSAND POETS | MUSICIANS FOR CHANGE - LOS ANGELES page: http://www.100tpcmedia.

About the Los Angeles Poet Society

Founded in 2010, the Los Angeles Poet Society, (LAPS), was by raised by East LA born Poet, Jessica M. Wilson. The mission of the LAPS is to create a bridge, fusing the communities of Los Angeles and Southern California Poets, poetry organizations, Writer groups, booksellers, publishers, literary enthusiasts and supporters into a unified social and literary network.

Our Mission

The focal point of LAPS is to network and publicize the events and achievements of its members. LAPS also organizes and promotes events, pulling from within its own community, to create and sustain Los Angeles’ literary anchor.

Membership into the Los Angeles Poet Society is always FREE. If you want to become a member, please sign up here: https://

Join the Los Angeles Poet Society

Let us be your bridge to Los Angeles Poetics!

Click HERE for your dip on in!

#publishers

#poets

#writers

#performancepoets

#spokenword

#readings

plus MORE!

Write Now!

Los Angeles Poet Society

2013 - 100 Thousand Poets for Change | Musicians for Change

Follow us: www.twitter.com/

YouTube: www.youtube.com/

Writers' Row

Poet Jessica M. Wilson, MFA

Follow Me: www.twitter.com/europawynd

YouTube: www.youtube.com/

Live Feed/U-Stream: http://www.

Thanks for participating!

Your Beyond Baroque Team

Tuesday, August 27, 2013

Steve Goldman Reading at Venice Library! Sponsored by Beyond Baroque!

AHOY ME HEARTIES!

STEVE GOLDMAN,

AND MAYHAP OTHERS FROM

BEYOND BAROQUE READ FROM MOBY

DICK,

WITH

A FEW APPOSITE SEA CHANTIES!

Saturday, September 21,

2013

Time:

4:00pm

Location:

Audience:

COME ALL YE!

Thursday, August 15, 2013

VENICE FAMILY CLINIC Art Walk and Auctions - Thursday, August 29th at 6:00 PM

Happy to promote:

VENICE FAMILY CLINIC Art Walk and Auctions:

THE 3rd ANNUAL SURF & SKATE SILENT ART AUCTION

Thursday, August 29th at 6:00 PM Auction Closes: 9 PM

ROBERT BERMAN GALLERY

ROBERT BERMAN GALLERY

At Bergamot Station Arts Center

2525 Michigan Ave. B7

Santa Monica, CA 90404

2525 Michigan Ave. B7

Santa Monica, CA 90404

|

| Laurie Steelink - SKATE DECK |

P.S. FYI, the VFC is suggesting a $15 donation, which will also get you a drink ticket, as well as a raffle ticket.

Thanks for your support and enjoy your summer!

Your Beyond Baroque Team

Sunday, July 28, 2013

PEN USA presents: TRANSLATION IN THEORY AND PRACTICE WORKSHOP

TRANSLATION IN THEORY AND PRACTICE

with David Shook

This workshop will introduce literary translation as an opportunity for participants

to engage a broader literary landscape and to study great writing across time and

language. Using close reading and cribs (languagecheat sheets ), participants will

produce their own translations of poems or short prose texts. Participants will then

workshop their new translations as a group. Discussion will range from the

theoretical to the practical, from experimental homophonic translation to how and

where to publish new translations.

to engage a broader literary landscape and to study great writing across time and

language. Using close reading and cribs (language

produce their own translations of poems or short prose texts. Participants will then

workshop their new translations as a group. Discussion will range from the

theoretical to the practical, from experimental homophonic translation to how and

where to publish new translations.

No knowledge of other languages required. Bilingual participants may bring

a poem or short text of their choosing.

a poem or short text of their choosing.

September 7, 2013 @ 10:00 AM - 1:00 PM

Located in Beverly Hills, CA. Address provided upon R.S.V.P.

Located in Beverly Hills, CA. Address provided upon R.S.V.P.

David Shook grew up in Mexico City before studying endangered

languages in Oklahoma and poetry at Oxford. He has published

translations or co-translations from the French, Gun, Isthmus

Zapotec, Kinyarwanda, Kirundi, Nahuatl, Portuguese, Russian,

Spanish, and Zoque. Recent books include Our Obsidian Tongues,

a collection of his own poetry, Shiki Nagaoka: A Nose for Fiction,

translated from the Spanish of Mario Bellatin, and the PEN International

Write Against Impunity anthology, featuring his translations of many

notable Latin American writers. He's translated manifestos by Roberto Bolaño and Oswald

de Andrade, and is editor of the Manifestoh!series of world literature manifestos in

translation for Insert Blanc Press. Shook serves as Contributing Editor toWorld Literature

Today andAmbit . He served as Translator in Residence at Britain’s Poetry Parnassus at

The Southbank in 2012, and is now International Editor of the Dhaka Translation Centre.

He's led translation workshops for the Poetry Translation Centre and Idyllwild Arts, and

has spoken on the subject at a wide range of literary conferences and events.

Shook lives in Los Angeles, where he edits Molossus and Phoneme Media.

languages in Oklahoma and poetry at Oxford. He has published

translations or co-translations from the French, Gun, Isthmus

Zapotec, Kinyarwanda, Kirundi, Nahuatl, Portuguese, Russian,

Spanish, and Zoque. Recent books include Our Obsidian Tongues,

a collection of his own poetry, Shiki Nagaoka: A Nose for Fiction,

translated from the Spanish of Mario Bellatin, and the PEN International

Write Against Impunity anthology, featuring his translations of many

notable Latin American writers. He's translated manifestos by Roberto Bolaño and Oswald

de Andrade, and is editor of the Manifestoh!series of world literature manifestos in

translation for Insert Blanc Press. Shook serves as Contributing Editor toWorld Literature

Today and

The Southbank in 2012, and is now International Editor of the Dhaka Translation Centre.

He's led translation workshops for the Poetry Translation Centre and Idyllwild Arts, and

has spoken on the subject at a wide range of literary conferences and events.

Shook lives in Los Angeles, where he edits Molossus and Phoneme Media.

General admission: $65.00, members: $45.00.

More info can be found on their website:

Best regards,

Your BB Team

Monday, June 24, 2013

Poetry Workshop : INTO THE HEART OF POETRY

We are happy to spread the word about this upcoming workshop!

INTO THE HEART OF POETRY

with Kim Rosen and Ellen Bass

October 27 – November 1, 2013

Mayacamas Ranch, Calistoga, CA

Join Ellen Bass and Kim Rosen for five days of living poetry. In this unique retreat, they will explore a combination of three elements: the inspiration of hearing poetry, the power of speaking poetry, and the craft of writing poetry. This workshop is equally appropriate for beginning and experienced poets, from those who are new to poetry to those who have published books or chapbooks. Or, if you are a teacher who could use a shot of inspiration or if you are someone in the helping and healing professions who would like to explore another way to reach the heart, this workshop could be for you. Though they'll focus on poetry, prose writers who want to be inspired by poetry and to enrich their language will find it a fertile environment.

For more details, please visit http://www.ellenbass.com/into-

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)